Most Plains Indian Tribe’s history were in oral traditions; told and shared from one generation to the next. Of the Plains Indians, only four tribes; the Kiowa, Lakota, Blackfeet and Mandan added to their oral storytelling tradition with picture markings of significant events that occurred to the tribe.

The tribes recorded their history in pictures.

Sai-Guat

The Kiowas called their picture recordings Sai-Guat, Winter Marks. Sai is the Kiowa word for year. A year goes from winter to winter. Guat was the Kiowa word for markings and eventually writing.

While most tribes noted a single event per year, the Kiowa’s picture calendars documented two events each year; one for summer and another for winter.

The calendar became a physical document used for time placements, memory aids and starting points for tribal linked stories.

Rather than using sequential numbers like the Western Calendar system, each entry was a significant event that marked and named the season. For example, the Winter of 1833-34 is recorded as “Winter the Night Stars Fell”.

Dohason’s winter marking of “The Night Stars Fell” matched with Western history’s winter of 1833-34 when all on the Great Plains woke to a meteorite shower that lit the night.

Kiowa Calendars Provide an Insider’s View

The Dohason and Anko Calendars recorded a crucial time in Kiowa history. Dohason began his calendar five years before the tribe’s first treaty with the United States in 1837 and extends thirteen years beyond the Kiowa’s tragic “Horse-Eating Winter” documenting the year buffalos were exterminated from the Plains.

The Dohason Calendar

The Dohason Calendar is the oldest sequential recording of Kiowa history.

Started by Chief Dohason, Little Bluff. He chronicled the tribe’s history from 1832 to the Winter of his death in 1865-66. He started it soon after the Kiowa’s great migration to Oklahoma. Dohason worried that future Kiowas would forget their distant past in the North Country.

Using pictures on a hide to record historical events was new to the tribe, but quickly embraced.

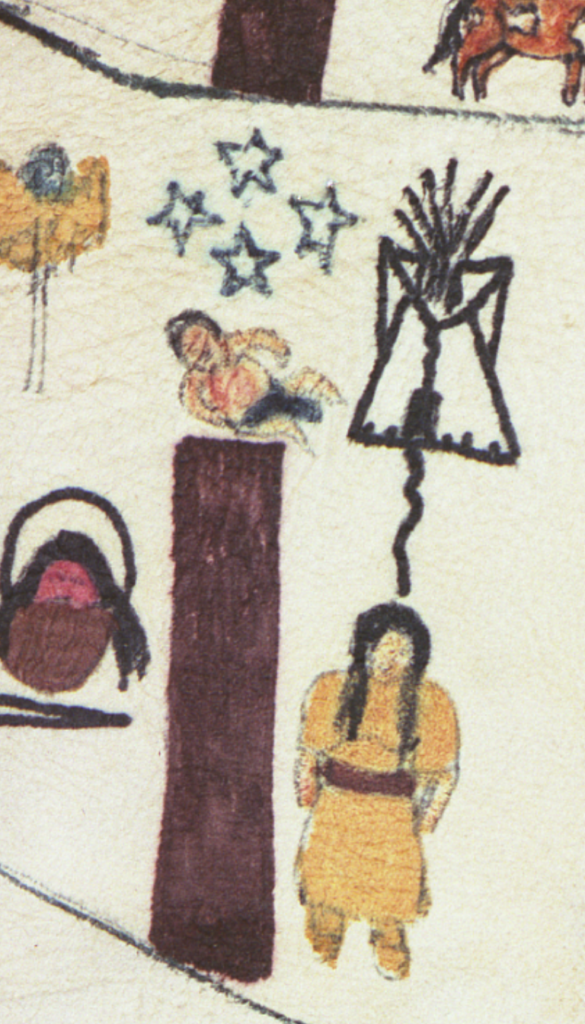

The Dohason Calendar begins at the lower right-hand corner and spirals inward, ending in the center. The pictographs tell Kiowa stories through name-glyphs, prominent figures, armed blue soldiers, chained Kiowas and burning tipis.

Anko Calendar

Another Kiowa calendar was created by Ankopa-ingyadete meaning “In The Middle of Many Tracks”, abbreviated to Anko. His Calendar chronicled the tribe’s final battles, relentless pursuit by calvary and early struggles on reservation life.

Anko’s Calendar is read down the middle, from left to right. Each year is noted by a black bar. Winter events are below the bar and Summer above the bar with a buffalo head representing the tribe’s Summer Sundance. Along the sides are additional monthly chronicles shown by a crescent moon and that month’s significant event.

Anko’s picture recordings covered Kiowa history from 1863 to 1892. His calendar showed a culture in transition, from free life in Kiowa Country to survival as prisoners of war.

Both calendars were used in tribe gatherings for extended storytelling. A pictured event sparked memories in other tribe members leading to more stories, linking family to family, generation to generation.

In this way Kiowas always know who they are, what they have survived and what it is to be Kiowa.

C. E. Rowell

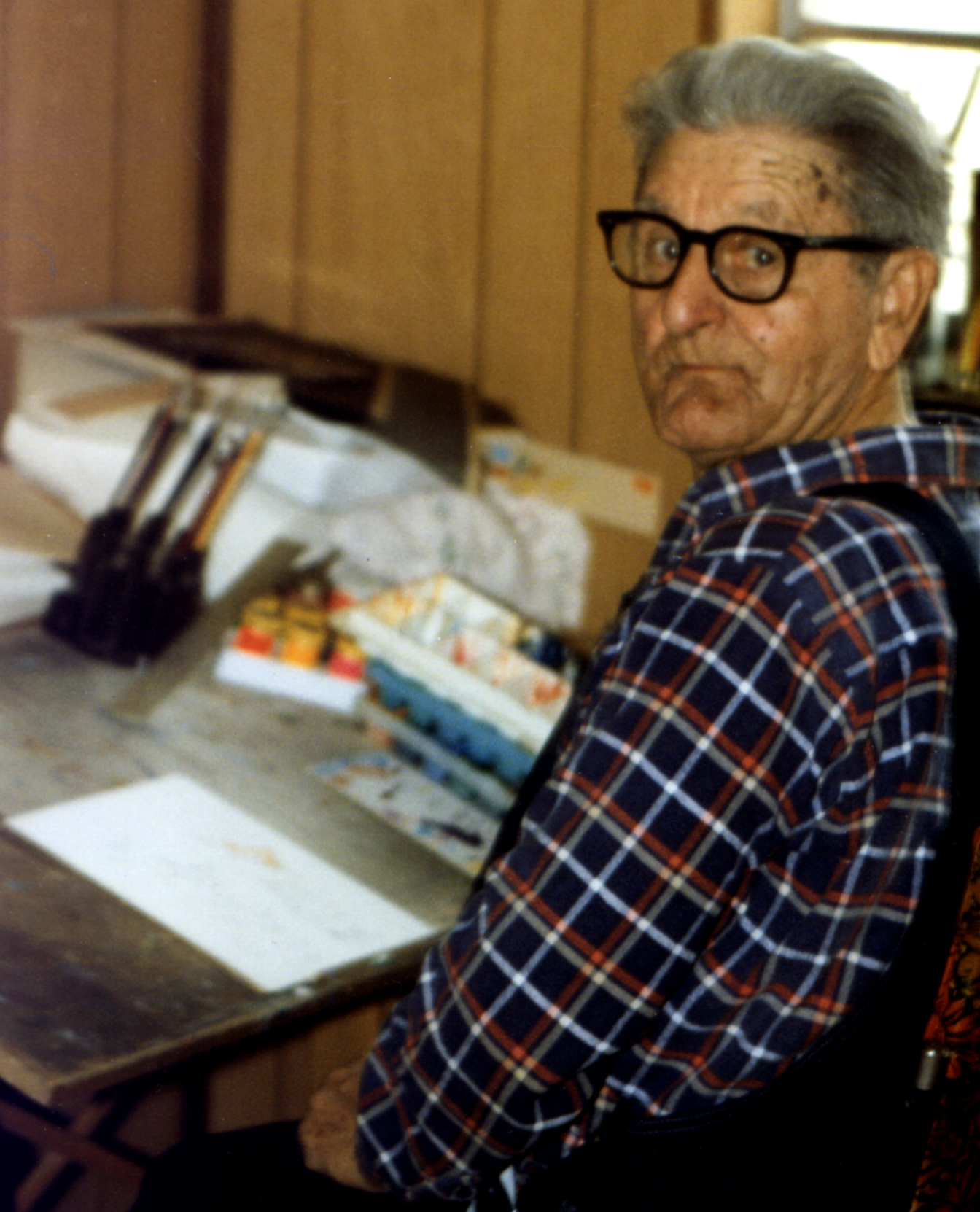

My Grandfather, C. E Rowell, was a Keeper of the two Calendars. Grandpa served as the tribe’s historian and was responsible for recounting the tribe’s history. He used the calendars to start stories at various gatherings.

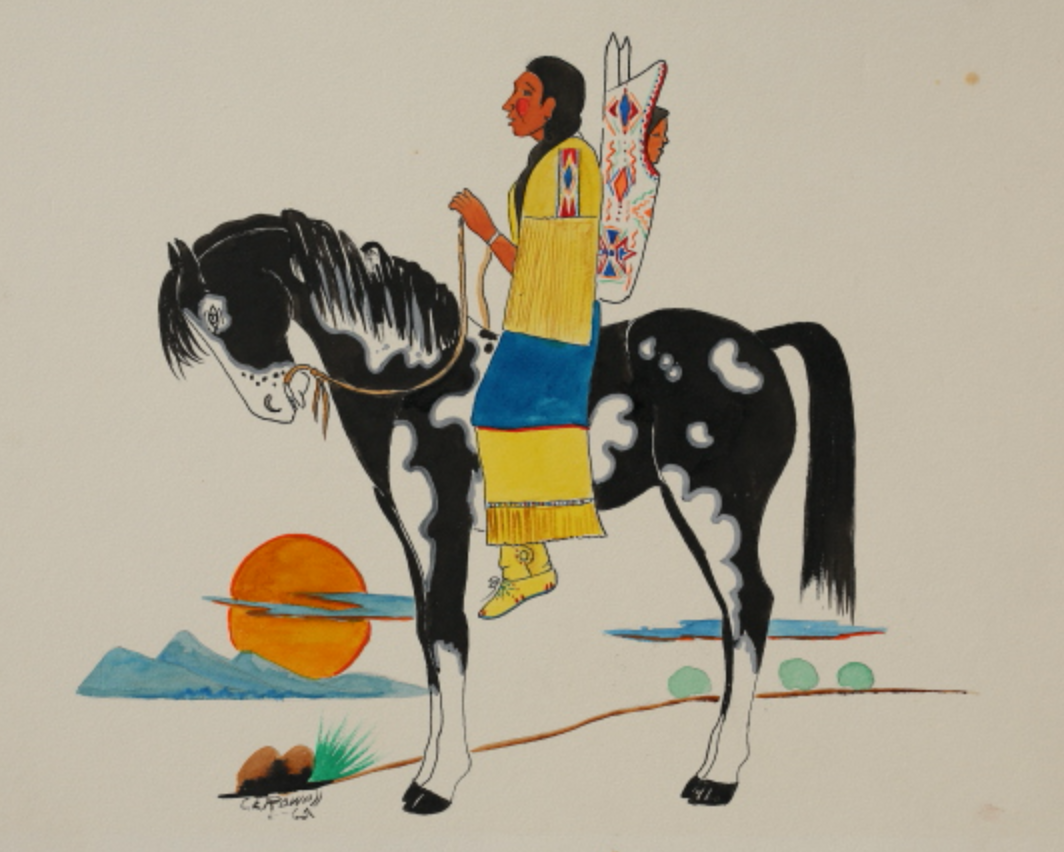

Like Dohason before him, Grandpa preserved Kiowa oral history in a new way. He added Kiowa history to his art.

Rowell’s vivid water color paintings depicted historical events and showed the tribe in authentic colors, traditional regalia and every day activities.

C. E. Rowell’s art is seen in museums and galleries across the Nation, including the Smithsonian National Museum.

Check back to learn more on C. E. Rowell and his paintings of Kiowa history in future blogs.